What is a CBDC?

Given the growing interest in Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs), most research and opinions begin by defining what a CBDC is—a concept that continues to evolve as major central banks issue their own digital currencies. The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) defines CBDCs as “a digital payment instrument, denominated in the national unit of account, that is a direct liability of the central bank.” Central to nearly all definitions is the emphasis that CBDCs represent a liability of the central bank, unlike deposit accounts, which are liabilities of commercial banks. Essentially, CBDCs function as digital dollars held in accounts at the central bank, underscoring their distinct nature as a direct obligation of the institution.

The rise of CBDCs is driven by various factors, including the declining use of cash, the rapid growth of cryptocurrencies, and the need for central banks to modernize payment systems in an increasingly digital economy. Their development aims to enhance financial inclusion, improve payment efficiency, and strengthen monetary sovereignty. However, the introduction of CBDCs also raises critical debates around privacy, potential disruptions to commercial banking, and risks of financial disintermediation. Globally, countries like China are pioneering CBDC pilot programs, while others, such as the European Central Bank and the U.S. Federal Reserve, are actively exploring their feasibility.

Wholesale vs. Retail

The two types of CBDCs under consideration serve distinct purposes and target different users. Wholesale CBDCs are limited to financial institutions and banks, facilitating interbank settlements and high-value transactions within existing central bank reserve systems. In contrast, retail CBDCs are designed for the general public, including businesses and consumers. They function as a digital equivalent of cash, offering privacy, transferability, convenience, accessibility, and enhanced financial security.

Aside from their general appeal, specific design features could determine the potential market share of CBDCs. For instance, a cash-like CBDC designed for everyday transactions has the potential to capture up to 23.3% of the payment market due to its appeal as a digital alternative to physical cash. Meanwhile, a deposit-like CBDC, functioning more like a traditional bank deposit, could secure approximately 18.45% of the market, offering users a secure and interest-bearing digital payment option. The widespread adoption of CBDCs would provide significant benefits, including greater accessibility and enhanced consumer participation in digital exchanges.

The 2024 critical review of CBDCs further classifies money, emphasizing the distinctions between digital currencies and traditional forms such as cash and commercial bank deposits. A key feature of CBDCs is their ability to function as either token-based or account-based systems, with designs tailored for wholesale, retail, or universal use without significant restrictions. Nonetheless, uncertainty remains regarding the seamless convertibility of CBDC accounts into other forms of money.

Receive Honest News Today

Join over 4 million Americans who start their day with 1440 – your daily digest for unbiased, fact-centric news. From politics to sports, we cover it all by analyzing over 100 sources. Our concise, 5-minute read lands in your inbox each morning at no cost. Experience news without the noise; let 1440 help you make up your own mind. Sign up now and invite your friends and family to be part of the informed.

Development Timeline

The Need for Research

Interest and research in CBDCs have grown rapidly since 2020. Major monetary authorities, including the Bank of Canada and the Federal Reserve, have published numerous working papers exploring the potential design of CBDCs and their implications for the future of monetary policy. The Bank of Canada, for instance, has published 136 papers since 2013 exploring digital credits or currencies issued by central banks. One of its earliest papers, published over a decade ago, examined the implications of Facebook Credits and the economics of digital currencies. The paper’s conclusion as we will come to discuss proved incorrect, it concluded: “We find that it will not likely be profitable for such currencies to expand to become fully convertible competitors to state-sponsored currencies.” (Gans et al., 2013). Patents for state-backed digital currencies, along with research articles and book chapters, have increased significantly as countries compete to be the first mover and safeguard their own currencies.

The Bank of Canada, like the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank, is focused on conducting extensive research on three key areas related to the introduction of a digital central bank liability:

Implications for the Commercial Banking Sector and Monetary Policy: Examining how a CBDC would impact the Commercial banking sector and influence the structure and effectiveness of existing monetary policy frameworks.

Design Features and Partnerships: Investigating the design of a CBDC, including identifying potential partners and determining how interest rates, insurance mechanisms, and public demand would be managed if such a currency were introduced.

Public Accessibility and Distribution: Exploring the approach for offering a CBDC to the public, particularly its similarities to traditional cash or bank deposits and how it would function as a cash-like instrument.

The Federal Reserve, exploring the feasibility of the digital currency, has outlined several guidelines for its potential introduction:

The CBDC would be a government liability, issued by the nation's central bank.

Any public introduction of the digital currency would require congressional approval.

No FDIC insurance would be provided, as this form of currency would be the safest and most liquid, with minimal liquidity risk, given that the U.S. dollar is a public monopoly owned by the Federal Reserve.

Commercial banks would likely play a role in intermediating accounts on behalf of the central bank.

A 2022 white paper from the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology demonstrates that a CBDC can be designed to handle an extremely high volume of transactions within a very short timeframe, proving its technical feasibility at scale. The processor's baseline requirements include a time to finality of under five seconds, a throughput exceeding 100,000 transactions per second, and robust geographic fault tolerance.

Speeding Up Adoption

The timeline for the Federal Reserve and other central banks to adopt digital currencies may be closer than it initially seemed. In 2020, digital payments accounted for 81% of all transactions in the United States. In Sweden, physical payments represented less than 10% of total transactions during the same period. The rapid shift to digital payments is undeniable; the only question is which major developed economy’s central bank will be the first to make a digital currency widely available?

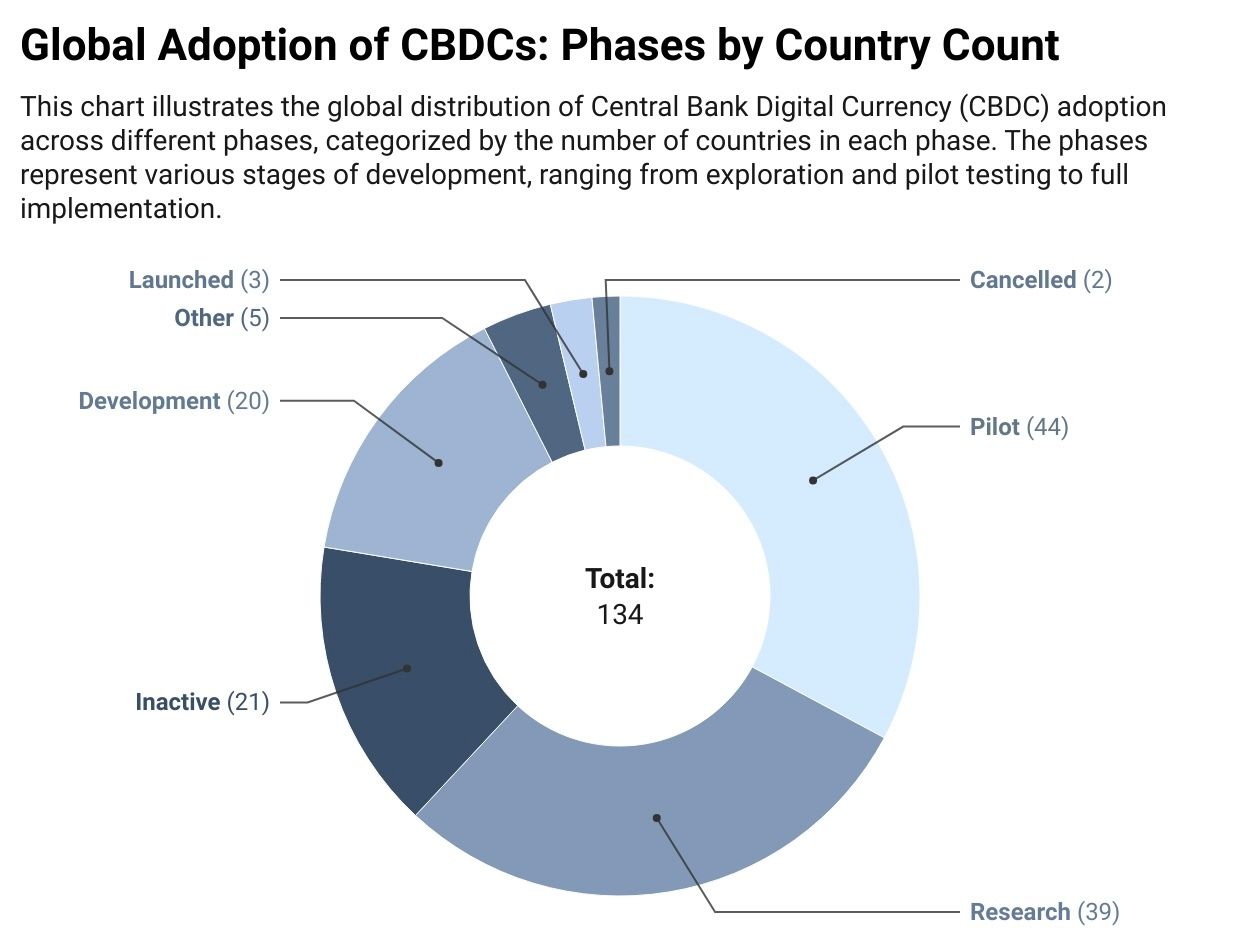

To address this question, we can turn to a comprehensive dashboard that tracks the global adoption of CBDCs and the development stages of each central bank. Most developed economies across the Eurozone, Asia, Africa, and North America are currently in the research or proof-of-concept phase, as illustrated in the figure below from CBDC Tracker. According to the Human Rights Foundation the majority of governments worldwide (62%) are actively researching, developing, or deploying CBDCs. As of late 2024, 134 countries and currency unions, representing 98% of global GDP, are exploring CBDCs—a significant rise from just 35 countries in May 2020.

Many monetary authorities are advancing into the proof-of-concept phase, supported by extensive research. On November 1, 2023, the European Central Bank (ECB) began a two-year preparation phase for the digital euro, focusing on laying the groundwork for potential issuance. Final implementation is not expected until 2028, pending legislative approval. The ECB is currently conducting a vendor selection process for €1.1 billion in contracts related to digital euro components. The project’s next major milestone is the publication of outcome reports in July 2025, which will highlight innovative use cases and conditional payments.

Launches So Far

According to the tracker, only a few countries have fully launched a CBDC. The limited number of these countries has encountered adoption challenges, a key issue highlighted in the current literature published by central banks, which aims to optimize interest-bearing accounts.

Nigeria 🇳🇬

The eNaira has faced significant adoption challenges, with reports showing that 98.5% of issued wallets remain unused. However, the system has processed over 2.2 million transactions worth approximately ₦108 billion, with 28.4 million wallets created.

The Bahamas🇧🇸

The Sand Dollar has encountered adoption challenges, prompting plans to require commercial banks to distribute the CBDC. As of December 2023, 118,955 personal wallets had been created, with approximately B$160,000 distributed through incentives and promotional efforts.

Jamaica 🇯🇲

As of late 2024, JAM-DEX has achieved limited adoption with approximately 260,000 wallet holders out of a 2.8 million population. Only one bank, National Commercial Bank (NCB), currently provides CBDC wallets through its Lynk application according to the Jamaica CBDC Tracker.

The Eastern Caribbean Currency Union 🇳🇱

The Eastern Caribbean Currency Union (ECCU) launched its CBDC, DCash, in March 2021, serving eight member countries: Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, Grenada, Montserrat, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines. As of 2023, DCash has achieved limited circulation, with over $900,000 in circulation, 21 participating financial institutions, 10 agencies, and nearly 400 merchants across all member countries.

The Bank of Japan is expected to decide on the introduction of a CBDC in just over a year, according to its proposed timeline. This would make it the first major global central bank to announce a definitive intention to launch a digital currency. Japan will also establish a CBDC forum, inviting private businesses involved in retail payments or related technologies to join the discussion.

The expansion of BRICS could prompt the United States to introduce a CBDC, especially as the group works to reduce reliance on the dollar as the world’s reserve currency. China, a founding BRICS member, has piloted the largest CBDC project, the digital yuan (e-CNY), according to the Atlantic Council. By June 2024, total transaction volume reached 7 trillion e-CNY ($986 billion) across 17 provincial regions in sectors such as education, healthcare, and tourism. This is nearly four times the 1.8 trillion yuan ($253 billion) recorded by the People’s Bank of China in June 2023.

Key Research

The development and piloting of CBDCs are ongoing, with significant research raising questions about the design and feasibility of cash-like deposits at central banks. Several highly cited papers in this field provide valuable insights into the challenges and potential impact of CBDCs on monetary policy.

A study by Andolfatto (2018) examines the theoretical implications of CBDCs on a monopolistic banking sector by combining models of government debt and banking. The findings suggest that interest-bearing CBDCs could enhance financial inclusion and reduce reliance on physical cash. While such CBDCs may reduce monopoly profits for banks, they do not necessarily lead to bank disintermediation. On the contrary, increased competition from CBDCs may compel banks to raise deposit rates, potentially boosting deposits. Although the framework is theoretical, it underscores the possibility of positive competition between CBDCs and traditional banking systems.

Expanding on the relationship between CBDCs and financial intermediation, Villaverde et al. (2021) explore scenarios where a central bank competes directly with private intermediaries for deposits. Their analysis highlights the stability advantages of a CBDC, especially during banking panics, as the central bank’s contractual rigidity with investment banks deters runs. This stability could position the central bank as a deposit monopolist, reducing the risk of bank runs but also challenging the traditional role of banks in maturity transformation. The study concludes that while CBDCs can replicate the outcomes of private intermediation under normal conditions, their impact on financial systems during crises is particularly significant.

The design of CBDCs also plays a crucial role in determining their effects on banking systems and monetary policy. Agur et al. (2022) explore how design choices, such as interest-bearing features and anonymity levels, influence individuals’ preferences for cash, CBDCs, and bank deposits. Their findings indicate that a deposit-like CBDC could reduce bank credit and output, whereas a cash-like CBDC might accelerate the elimination of physical cash. Optimal CBDC design requires balancing the need for bank intermediation with maintaining diverse payment options, particularly when network effects significantly impact payment preferences.

Finally, Davoodalhosseini (2022) investigates the welfare implications of CBDCs in the context of optimal monetary policy. This Bank of Canada study finds that a low-cost CBDC could achieve efficient allocations, potentially surpassing cash in welfare outcomes. However, offering both cash and a CBDC might reduce overall welfare compared to scenarios where only one payment option is available. Estimated welfare gains from introducing a CBDC in the United States and Canada suggest modest increases in consumption, depending on the transaction costs associated with the CBDC. These findings highlight the importance of carefully assessing usage costs and design elements to maximize the societal benefits of CBDCs.

Interest Bearing vs. Non-Interest Bearing

Impact on The Financial System

An interest-bearing CBDCs can significantly influence deposit market dynamics by acting as a floor for bank deposit rates, compelling banks to offer more competitive rates to retain deposits. Higher CBDC interest rates have the potential to increase overall deposit levels and bank lending by up to 2%, which could enhance economic output by approximately 0.2%.

Contrary to concerns about financial disintermediation, interest-bearing CBDCs can actually foster bank intermediation by incentivizing banks to raise deposit rates as previously discussed. While banks can mitigate competition from CBDCs by matching their interest rates, this strategy often comes at the expense of reduced profit margins.

Monetary Policy Implications

Interest-bearing CBDCs have the potential to enhance monetary policy transmission by giving central banks more direct control over interest rates. This capability could help overcome the zero lower bound constraint, enabling the implementation of negative interest rates during economic crises. However, the digital currency may also reshape market structures, affecting banks of different sizes in varying ways. Higher CBDC interest rates could increase the market share of large banks, while posing challenges for smaller banks to remain competitive. Moreover, setting CBDC rates too close to the IOR rate may lead to a concentration of deposits in larger banks, further altering the competitive landscape.

There’s a reason 400,000 professionals read this daily.

Join The AI Report, trusted by 400,000+ professionals at Google, Microsoft, and OpenAI. Get daily insights, tools, and strategies to master practical AI skills that drive results.

Congratulations on making it to the end, while you’re here enjoy these other newsletters and be sure to subscribe to The Triumvirate before you go.

Interested in How We Make Our Charts?

Some of the charts in our weekly editions are created using Datawrapper, a tool we use to present data clearly and effectively. It helps us ensure that the visuals you see are accurate and easy to understand. The data for all our published charts is available through Datawrapper and can be accessed upon request.