What is Market Monetarism?

The traditional dogma of monetary policy focuses on targeting inflation and unemployment through tools available to central banks, such as short-term interest rates, forward guidance, and large-scale asset purchases. A modern approach to monetary policy, rooted in Milton Friedman’s M2 targeting theory, is the idea of targeting Nominal GDP as a way to guide the economy. This approach aims to control both inflation and real output growth simultaneously. Furthermore, the idea relies on policymakers using real-time market indicators to inform the policy path, rather than relying on lagging indicators. By using market indicators—assuming accurate price discovery—central banks can respond more quickly to supply and demand shocks in the economy. These principles form the foundation of the “Market Monetarism” school of economic thought.

Understanding Nominal vs. Real GDP

According to Sumner, the problem is fundamentally nominal. Nominal GDP (NGDP) represents the total dollar value of all goods and services produced domestically over a given period. In contrast, Real GDP (RGDP) adjusts nominal GDP by factoring out changes in the price level or inflation. Sumner highlights that nominal GDP is essentially a monetary concept, visualized as dollar bills. On the other hand, Real GDP represents the physical economy—factories, office buildings, homes, and workers providing services.

An illustrative example of the difference between NGDP and RGDP is Zimbabwe in 2008, where RGDP plummeted during a recession while NGDP soared at one of the fastest rates globally. Similarly, in the United States during the 1970s, NGDP growth reached double digits, despite RGDP growth remaining around 3%, lower than in the 1960s. This clearly demonstrates that NGDP and RGDP are distinct concepts.

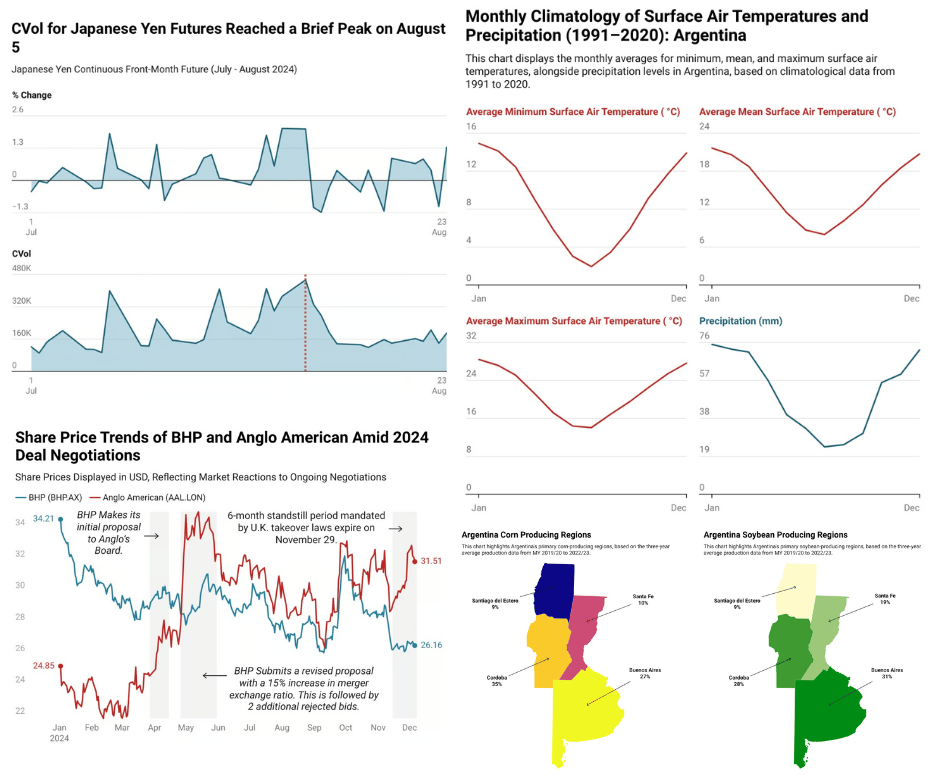

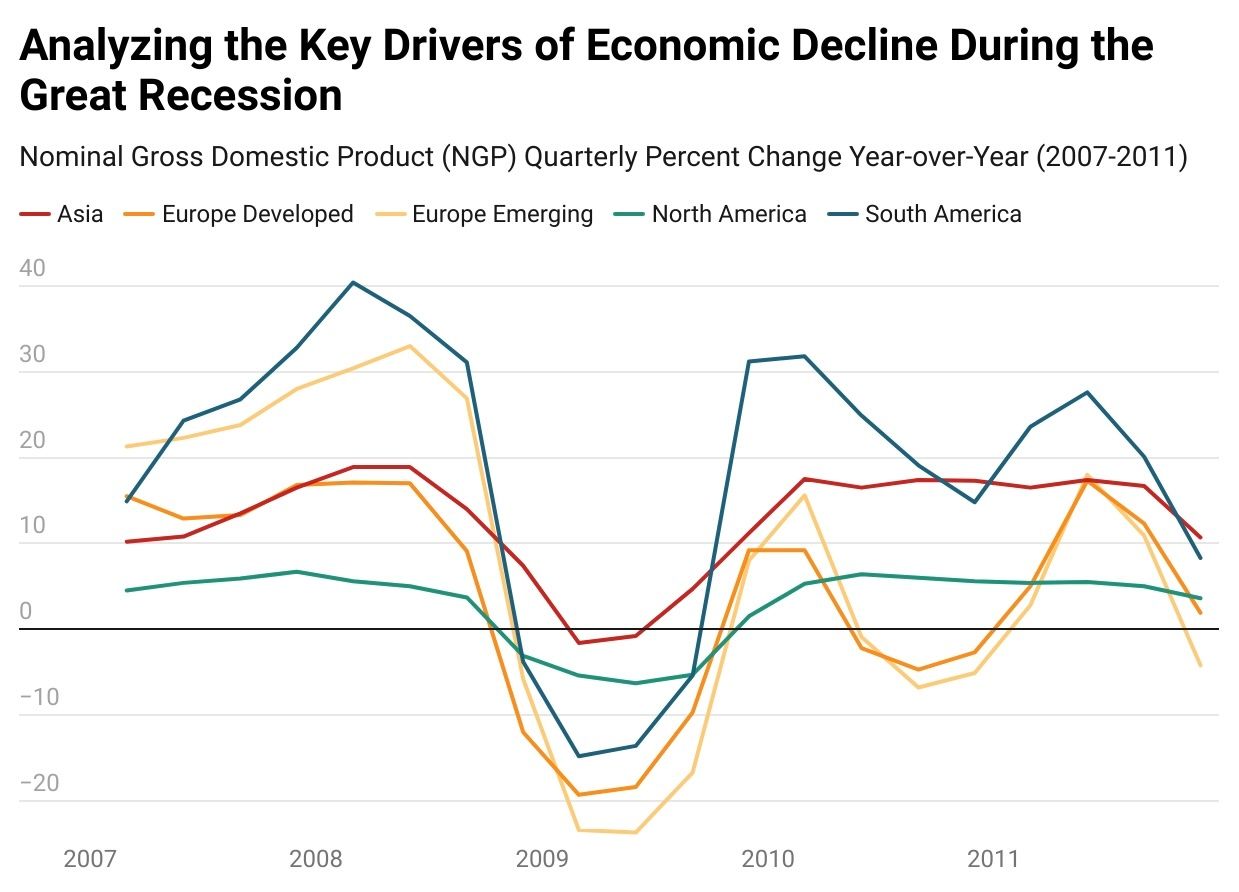

The figures below illustrate there was a sharp decline in nominal GDP growth at the onset of the Great Recession across global economies both emerging and developed. Many market monetarists contend that if monetary policy had targeted nominal GDP growth as opposed to the price level, the downturn could have been mitigated more effectively.

Source: FactSet

Source: FactSet

The term “Market Monetarism” which is associated with Nominal GDP targeting was coined by Danish economist Lars Christensen in 2011, with economists such as Scott Sumner and David Beckworth advocating for the idea. The theory gained attention after the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, as economists linked the severity of the crisis to the overly tight monetary stance of central banks during that period. While we will defer to the experts on the plumbing of market monetarism, below you will find the case for nominal GDP targeting as a framework, along with the arguments from both sides presented to date.

A Message From our Sponsor

Bullseye Trades

Trade Smarter with these Free, Daily Stock Alerts

It’s never too late to learn how to master the stock market.

You’ll receive daily trade alerts sent directly to your phone and email detailing the hottest stock picks.

The best part? There’s no cost to join!

Expert insights will be at your fingertips instantly.

Nominal GDP Targeting

What is it?

Market monetarists advocate for targeting nominal GDP to control inflation, as an alternative to traditional inflation targeting. Nominal GDP targeting focuses on both real and nominal variables. The central bank would aim for a specific growth rate in the level path of nominal GDP, typically around 4-5% per year. With an inflation target of 2%, this would imply real GDP growth of 2-3%, effectively targeting both inflation and real output simultaneously. Central banks would then adjust the policy rate to respond to deviations in nominal GDP growth, addressing inflation and spending growth relative to potential economic output.

Rooted in the Quantity Theory of Money or So we Think?

The basis for nominal GDP targeting is actually rooted in the equation of exchange (it is actually an identity), expressed as:

M * V = P * Y

Where:

• M is the quantity of money,

• V is the velocity of circulation,

• P is the price level,

• Y is the real output.

In other words, P * Y represents nominal GDP. Under nominal GDP targeting, a central bank would commit to maintaining a certain level of spending by adjusting M * V . However, since velocity ( V ) is an unobservable factor in the economy, its influence must be inferred or assumed.

This is not to be confused with the Quantity Theory of Money which predicts a one-for-one relationship between the change in the growth rate of money and the change in the rate of inflation or price level.

In his 2021 book The Money Illusion, Scott Sumner illustrates the link between nominal income and inflation resulting from changes in monetary policy. The example provided highlights how monetary policy influences both inflation and nominal income. Periods of high inflation are typically caused by rapid money supply growth, and even at lower inflation rates, monetary policy plays a key role in determining inflation and nominal GDP growth. A permanent increase in the money supply leads to a proportional rise in both prices and nominal GDP over time.

The example uses Roger, who earned $76,000 in 2019, to illustrate this effect. Had the U.S. remained on the gold standard originally abolished by FDR in 1933, Roger’s nominal income would be around $4,000, but his purchasing power would remain the same because prices would be proportionally lower. This demonstrates how changes in monetary policy affect nominal figures without necessarily altering real economic value.

This example ties directly to the equation of exchange examined above, which states that the money supply (M) multiplied by the velocity of circulation (V) equals the price level (P) times real output (Y), or M * V = P * Y.

In Roger’s case, the significant increase in prices after the U.S. abandoned the gold standard in 1933 illustrates how an expanded money supply (M) raised the price level (P), while real output (Y) stayed relatively stable. His income of $76,000, compared to the hypothetical $4,000 under the gold standard, shows how nominal values are shaped by monetary expansion. However, because prices would also be lower under the $4,000 scenario, Roger’s real purchasing power, tied to real output (Y), remains unchanged.

It is not a new concept but Nominal GDP Level Targeting (NGDPLT) has grown in the past decade and a half following the great recession. Although no central bank has formally adopted nominal GDP targeting as their policy anchor, both the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England have acknowledged it. In 2013, the Bank of England considered the framework but ultimately decided against it. Similarly, the Federal Reserve has discussed nominal GDP targeting as a potential alternative framework, though it has not been implemented.

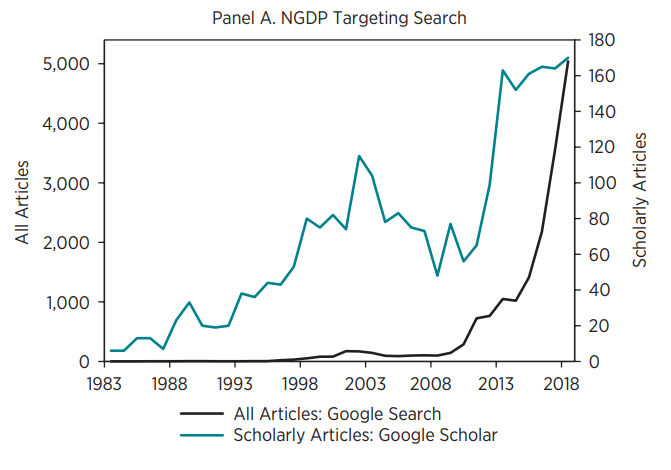

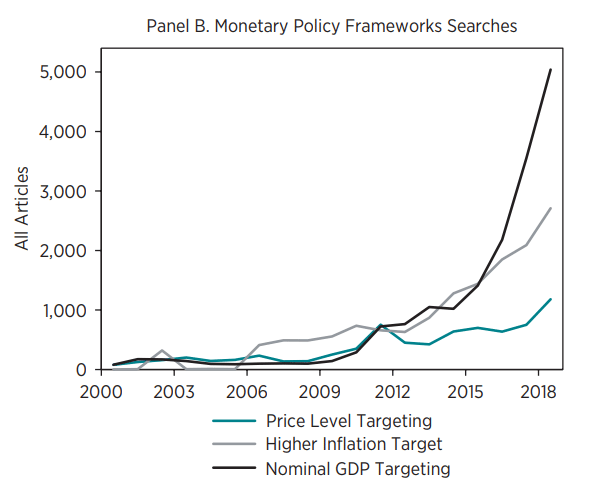

Beckworth’s paper, which summarizes the facts and fallacies of the policy framework, highlights its growing popularity, as shown by increasing Google Scholar and Google search trends. While the subject has long been of interest to economists and researchers, it has recently gained traction in mainstream searches—particularly the term "Nominal GDP Targeting," as illustrated in Panel B.

The question of what monetary policy truly entails remains unresolved, especially when considering the real-world implementation of nominal GDP targeting as a framework beyond theoretical models. Could it offer a better alternative to the Taylor Rule or inflation targeting? Economists such as James Meade, James Tobin, and more recently Scott Sumner, Marc Nunes and Lars Christensen(through blogging since the Great Recession) have advocated for central banks to adopt this approach. However, others, including John Cochrane and James Bullard of the St. Louis Fed, have highlighted concerns and potential issues with this policy.

John Cochrane outlined several objections to NGDP targeting in a blog post from the Grumpy Economist:

Unclear how the Fed would actually hit an NGDP target operationally

Assumes potential GDP growth is constant or slow-moving, which may not be true

Less clear than a price level target for economic actors

GDP measurement issues could be problematic

James Bullard of the St. Louis Fed mentioned no central banks have actually adopted NGDP targeting, partly because:

It hasn't been tried in practice

May be harder to communicate to the public than inflation targeting

Switching frameworks again after recently adopting inflation targeting could be disruptive

Select Arguments For

Naturally, there are quite a few arguments for nominal GDP targeting, now more than when select economists first challenged the status quo.

Effective Performance: Nominal GDP targeting generally performs well in economic models according to a 2015 National Bureau of Economic Research paper , resulting in minimal welfare losses and closely aligning with flexible price and wage allocations.

Comparison with Alternatives:

Taylor Rule: Nominal GDP targeting leads to smaller welfare losses compared to an estimated Taylor rule.

Inflation Targeting: It significantly outperforms inflation targeting in terms of welfare outcomes.

Relative Performance:

Wage Stickiness: Nominal GDP targeting performs best relative to alternative rules when wages are sticky compared to prices and in the context of supply shocks.

Output Gap Targeting: While output gap targeting consistently outperforms nominal GDP targeting, the differences in welfare losses between the two are minor.

Real-Time Measurement: Nominal GDP targeting may yield lower welfare losses compared to output gap targeting if the central bank struggles with real-time measurement of the output gap.

Equilibrium Determinacy: Nominal GDP targeting always supports a determinate equilibrium, whereas output gap targeting might lead to indeterminacy if trend inflation is positive. Equilibrium determinacy supports the case for NGDPLT because the policy framework targets overall spending in the economy, encompassing both inflation and real output. This ensures that fluctuations in either inflation or output are balanced.

Select Arguments Against

A recent study in 2021 from the Department of Economic and Scientific Policy at the European Parliament lays out key counterarguments for the framework.

Similarity to Flexible Inflation Targeting: NGDP targeting closely resembles flexible inflation targeting, where interest rates respond to inflation deviations and the output gap, similar to a Taylor-type rule. NGDP targeting might already be implicitly implemented, making a formal institutional shift unnecessary.

Level vs. Growth-Rate Targeting: NGDP targeting can be based on a level or growth rate. Targeting the level works as an "error-correction" mechanism, but if expectations aren't aligned between the public and the central bank, it could increase NGDP variability and impose economic costs.

Communication and Transparency Issues: NGDP is less tangible and harder for the public to understand compared to consumer price indexes, which are more relatable. NGDP is also subject to revisions, complicating communication and potentially undermining the central bank's credibility, especially if the target must be frequently adjusted.

Social Preferences: The composition of nominal growth (inflation vs. real growth) is not considered in NGDP targeting. However, social preferences may prioritize one over the other, suggesting a need for asymmetry in policy responses.

Financial Stability Concerns: NGDP targeting overlooks the objective of financial stability. Some argue that central banks should adopt a broader mandate, incorporating financial stability alongside price stability and economic performance, potentially through a triple mandate approach.

The communication and transparency argument is crucial. Most people are not economists advocating for NGDP targeting; they want to easily understand how the economy functions and what it means for prices. Transparent communication from the central bank is essential to ensure the public comprehends the target and its implications.

Putting it into Practice

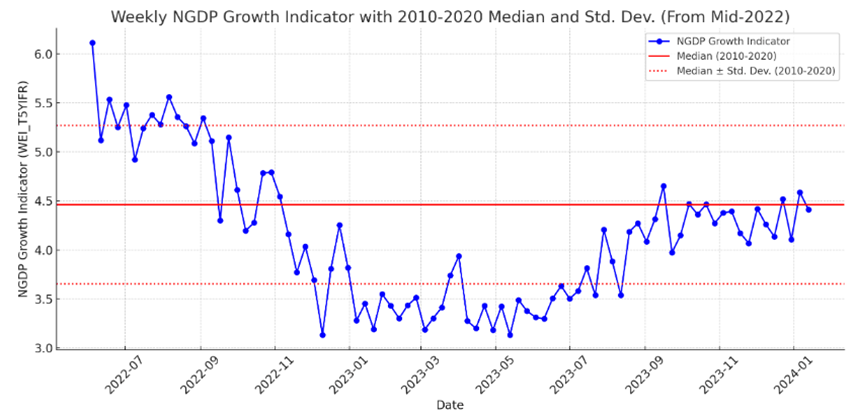

While NGDPLT is conceptually straightforward—acting as a growth-path target that can address both supply and demand shocks—demonstrating its effectiveness in practice is challenging, making it unlikely to become the dominant monetary policy framework for now. Lars Christensen in his ‘The Market Monetarist’ blog discusses how the Federal Reserve has maintained a steady 4.5% growth rate in NGDP from Mid-2022 and cites that the central bank will over time be able to deliver on its 2% inflation target due to this stable NGDP growth but again the Federal Reserve was not directly targeting overall spending.

Critics of NGDPLT often point to issues of public understanding and the similarities to existing policies such as the ones discussed above. Another challenge is how a central bank would actually target nominal GDP. This is where the idea of an NGDP futures market becomes relevant. Given the quarterly release, potential lag, and frequent revisions to NGDP data, accurately tracking it is difficult—unless an instrument, such as NGDP futures, could be used to achieve the target.

Nominal GDP Futures Market

The Framework

Scott Sumner who has an abundance of resources on NGDP targeting has proposed the creation of an NGDP futures market that the Federal Reserve could use to target nominal GDP growth. The idea behind this framework is to set the monetary base at a level where market expectations of future NGDP growth align with the desired target.

The Fed would commit to buying and selling NGDP futures contracts (cash settled) at a target price (e.g., $4000), using market forecasts to guide the optimal setting of monetary instruments. Proponents argue that this approach avoids circularity problems, as the key is not for markets to predict future NGDP directly, but to forecast the instrument setting that would result in on-target NGDP growth (e.g., 5%).

Central Bank Involvement

Under this proposal, the Federal Reserve would actively participate in the NGDP futures market by buying and selling contracts to control the money supply. This involvement would help offset changes in velocity, ensuring that NGDP growth remains on track. The Fed’s commitment to buying and selling unlimited quantities of NGDP futures contracts would effectively rely on market forecasts to adjust monetary policy in real time.

Sumner makes the point that it is an advantage that such a market does not already exist giving the Federal Reserve the chance to build the contract to achieve its respective goals of targeting. The paper highlights three key characteristics that make a futures market successful:

Volatility of the underlying asset value

A large number of market participants who want to hedge such volatility and

A contract design that allows those interested in hedging to do so successfully

For the purposes of targeting solely based on a forward policy level, the first two criteria would make the system less effective cites Sumner.

Example

The Fed would offer to buy or sell unlimited quantities of NGDP futures at a price of $1.0365, which reflects a 3.65% expected GDP growth rate. When the contracts mature in one year, their value will be determined by the ratio of next year's nominal GDP to current nominal GDP.

1. If nominal GDP increases by only 2%, short position holders would profit $0.0165 per contract, while long position holders would incur the corresponding loss.

2. If nominal GDP rises by 5%, the contracts would be worth $1.05. Long position holders would earn $0.0135 per contract, while short position holders would lose that amount.

In principle, the purchase and sale of NGDP futures contracts could act as a sort of “open market operation” that directly impacts the size of the monetary base and hence expected future NGDP

As an alternative, some have suggested that the Fed could use existing forecasts, such as those from the Survey of Professional Forecasters, within a Taylor-rule type framework. However, the NGDP futures market represents a more dynamic and market-driven solution for guiding central bank policy.

Regulatory Oversight

There are concerns about potential issues such as market liquidity and speculative bubbles within the NGDP futures market. While critics have raised these concerns, proponents argue that these issues are unlikely to pose significant risks specifically for NGDP futures due to the oversight of the Federal Reserve it one were to be constructed in the United States.

In terms of oversight, this framework would require close regulation and monitoring to ensure the market functions efficiently and is resistant to manipulation or instability. Regulatory bodies such as the Commodities and Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) would need to establish rules that prevent abuses while enabling the market to provide accurate signals for monetary policy.

New markets and instruments, especially prediction markets, are being approved daily. For example, on September 12, 2024, Bloomberg reported that a federal judge ruled in favor of Kalshi, a prediction platform, allowing the company to offer up to $100 million in wagers on the outcome of the 2024 congressional elections. This decision dealt a significant blow to the CFTC, which had been attempting to curb the growing popularity of election-related derivatives trading. The idea of having the ability to predict yet another economic data point does not seem far off.

Alternatives and Prevailing Usage

Inflation Targeting

Inflation targeting is a monetary policy strategy where central banks aim to achieve a specific inflation rate. The Bank of New Zealand, considered a pioneer in this approach, was the first to implement this strategy. According to research by Cbonds there are currently 55 countries in which central banks set explicit inflation targets. Not all inflation targets are the same of course and some monetary authorities will target different measures of inflation .

For example the Federal Reserve will target Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) inflation while the ECB targets the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP). The HICP includes rural populations while the PCE will focus only on urban residents which omit 13% of the U.S. population. HICP also excluded owner-occupied housing costs in the measure of the price level including updates made to weights annually based on consumer spending patterns.

Taylor Rule and Influence on Policy

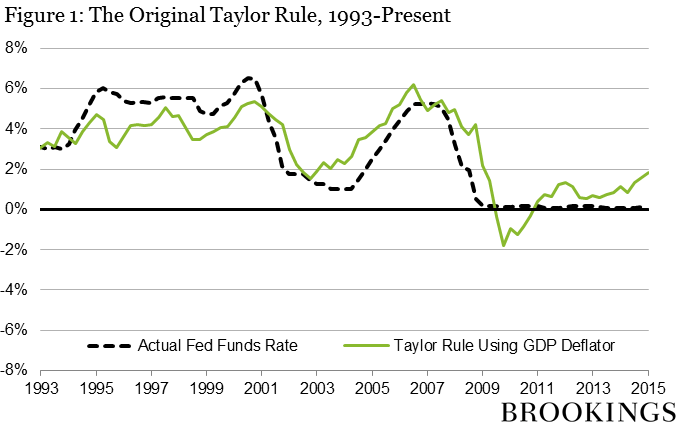

The Taylor Rule developed by economist John B. Taylor in 1992, is a monetary policy guideline that links the federal funds rate to inflation and changes in real income (nominal income adjusted for inflation). Many central banks will use the Taylor Rule as a cross-check and a key part in the policy framework but it is not followed mechanically. The issue with the Taylor rule is its oversimplification in using only a few variables as well as it assumes that policymakers know and can agree on the size of the output gap (difference between the economy’s potential and actual output). According to a report from Brookings monetary policy conducted from 2011-2015 by the Federal Reserve was somewhat ‘too easy’ if the Taylor Rule below was used as the benchmark.

Further studies such as the one attached below links the Taylor Rule to nominal GDP targeting using U.S. data. The authors demonstrate that forecast errors by the Federal Reserve can account for up to 13 percent of fluctuations in the output gap. Additionally, the simulations indicate that a nominal GDP targeting rule would lead to lower volatility in both inflation and the output gap compared to the Taylor Rule under conditions of imperfect information.

Is There Any Real Evidence?

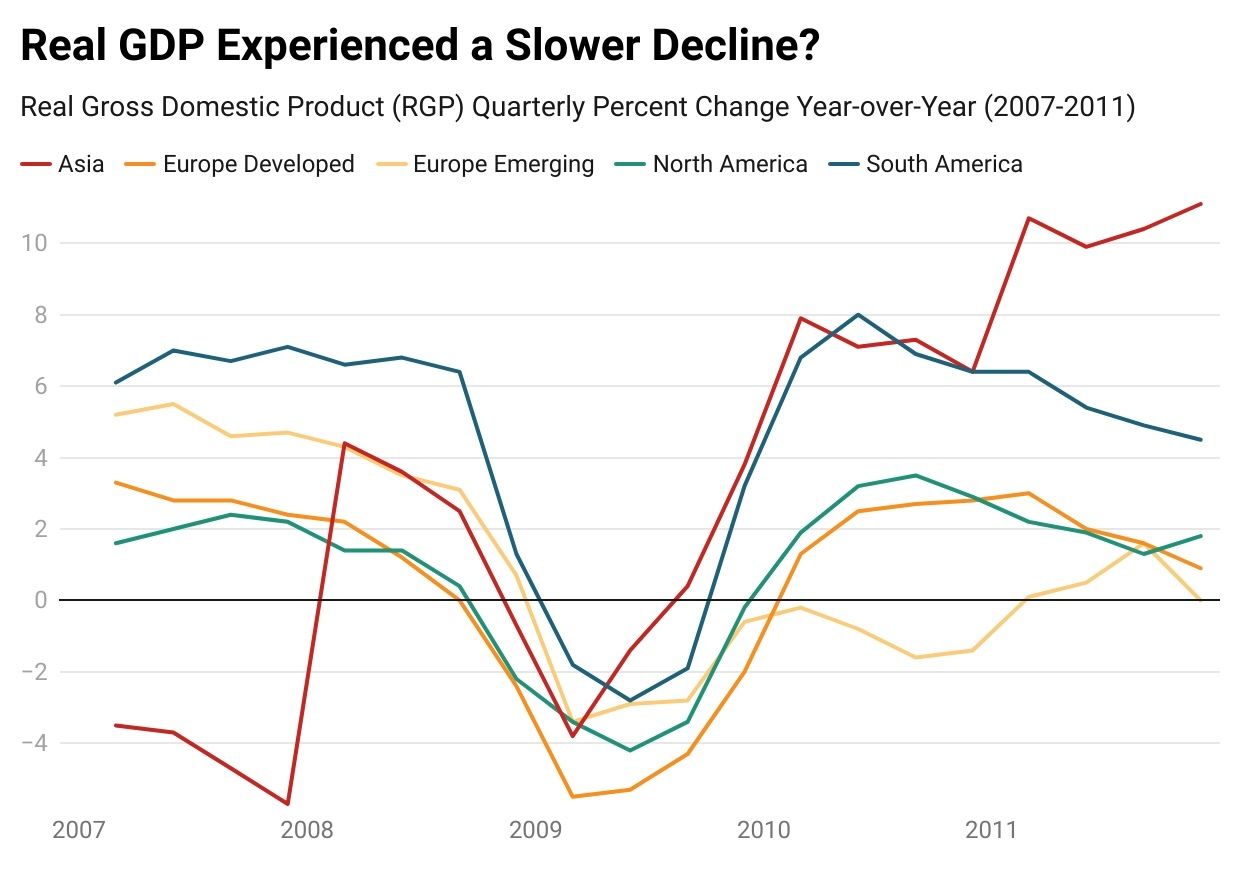

It’s hard to find real-world evidence for a framework that remains largely theoretical. The paper below investigates the optimal size of the nominal GDP target, presenting evidence that supports a 5% target although some argue for even lower or higher growth rates based on the table below.

Source: Murphy & Chen (2016)

However, the research struggles to find consistent evidence for the effectiveness of level targeting. Remember level targeting is a specific approach where policymakers aim to bring the economy back to a predefined nominal GDP path if it deviates. The model examines individual countries like Austria, Sweden, and Norway, none of which provide solid evidence of successful level targeting. The authors also question whether level targeting is even an appropriate measure.

This is just one example of in the past decade of the work that is being done to shed more light on the policy framework that may not be far from our future. Ultimately only policymakers can be the first mover in putting the framework into practice.

Interested in How We Make Our Charts?

Some of the charts in our weekly editions are created using Datawrapper, a tool we use to present data clearly and effectively. It helps us ensure that the visuals you see are accurate and easy to understand. The data for all our published charts is available through Datawrapper and can be accessed upon request.