The Odd Man Out?

The Swiss National Bank (SNB) is currently the only major central bank actively responding to outright deflation. With inflation running below its 0–2% target range and projected to remain subdued for years, the SNB has signaled it may even return to negative interest rates if deflationary pressures persist—a scenario markets are increasingly pricing in after the Swiss National Bank says its policy rate would drop to zero from 0.25% in late June.

This stands in sharp contrast to central banks like the ECB, Federal Reserve, and Bank of Japan, which are still grappling with inflation rates at or above their targets. For these institutions, recent or anticipated rate cuts are focused on managing disinflation and supporting growth, not combating falling prices. The SNB’s situation is unique, as most advanced economies are not currently facing the threat of persistent deflation.

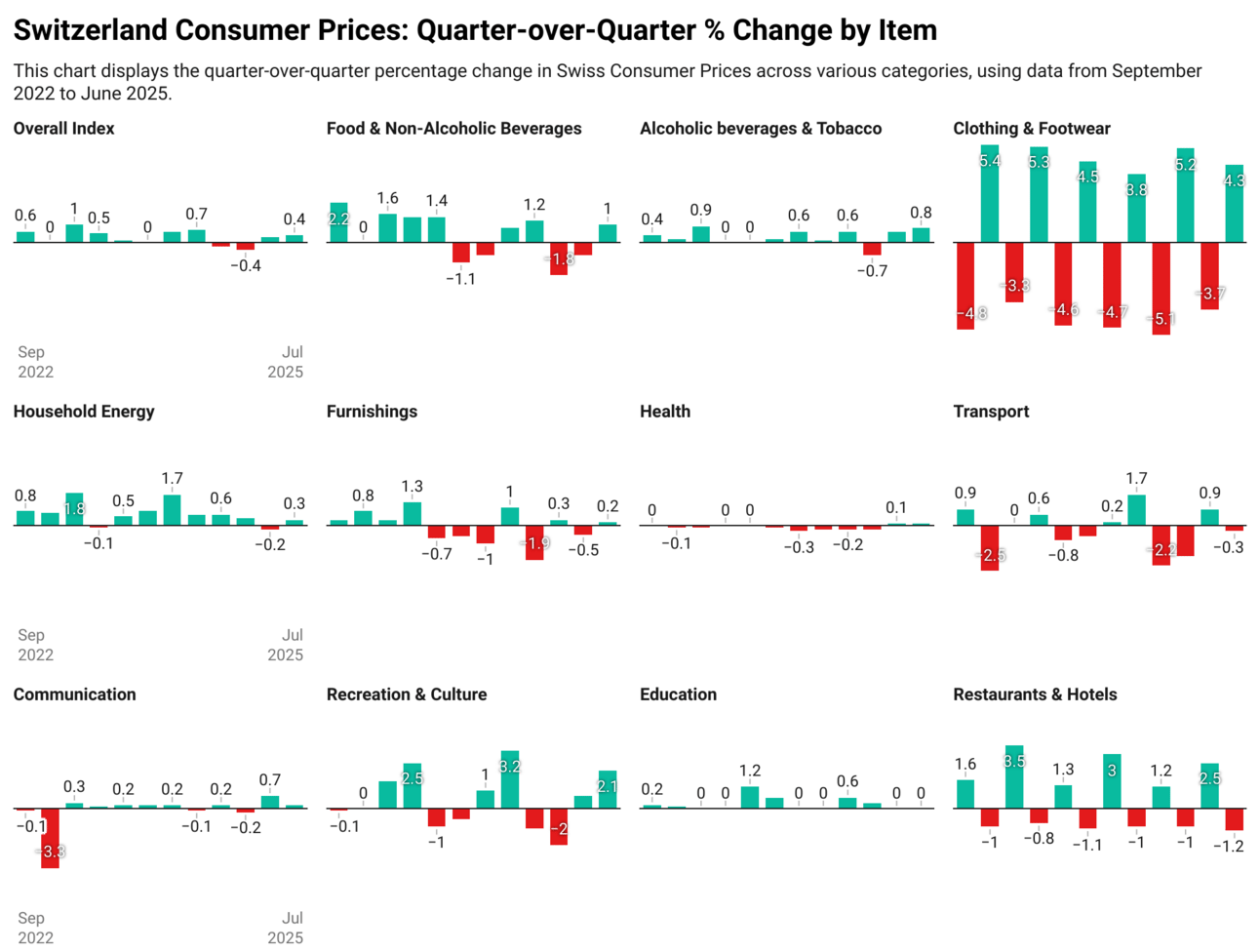

Swiss annual inflation edged slightly higher in June but remained near deflationary territory, keeping the door open for a potential policy shift. Consumer prices rose just 0.1% year-over-year, up from May’s -0.1%, according to Switzerland’s statistics office. Bloomberg reports that June’s inflation was primarily driven by holiday-related expenses, while prices for gasoline, air transport, and stone fruits declined. Core inflation, which strips out volatile components like fresh produce, seasonal goods, and energy, increased by 0.6%.

Source: Swiss Federal Statistics Office, Swiss National Bank

Thomas Junius, an economist at Safra, pointed out that a Europe-wide heat wave contributed to a 3% rise in Swiss food prices in June—an unusually large increase compared to previous years. In contrast, consumer price growth in the surrounding euro area remains significantly stronger, with inflation hitting 2% in June—the ECB’s medium-term target. On the EU’s harmonized inflation measure, Swiss prices rose just 0.2% over the same period.

Deflation has become a tangible reality in Switzerland, prompting aggressive monetary easing by the SNB. In response to falling prices and a strengthening franc, the central bank has adopted a zero interest rate policy (ZIRP) to stimulate the economy and stabilize inflation. However, this leaves limited room for further conventional easing. Committed to maintaining price stability, the SNB stands ready to act further, including potential currency interventions and a return to negative interest rates if necessary.

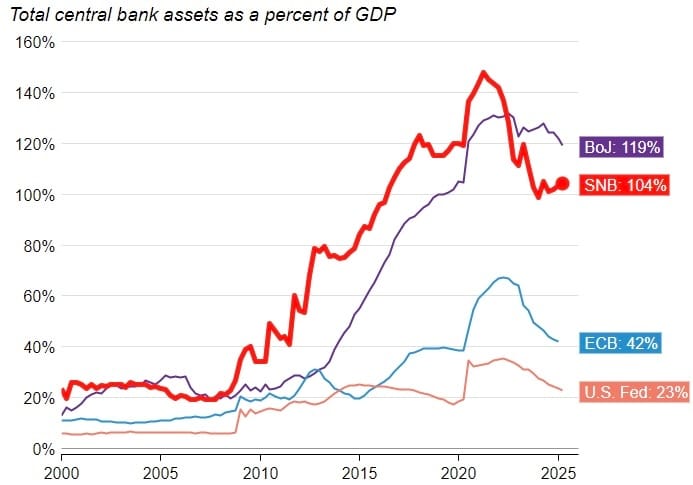

Swiss Franc to Blame?

According to a Reuters report from early June, the Swiss National Bank (SNB) may soon be forced to resume selling francs and expanding its balance sheet to counter deflationary pressures. It has been down this path before: between 2010 and 2022, the SNB’s balance sheet ballooned nearly tenfold, peaking at over 1 trillion francs (approximately $1.3 trillion). Although it has since contracted to 843 billion francs, it still exceeds the size of Switzerland’s annual GDP and is more than four times larger than the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet relative to the size of the U.S. economy.

Why Can Surging Exchange Rates Lead to Deflation

A strengthening Swiss franc can drive deflation in Switzerland through several key channels:

Cheaper imports: A stronger franc lowers the cost of imported goods and services, reducing overall consumer prices.

Weaker exports: Swiss goods become more expensive abroad, hurting demand and slowing economic growth.

Lower inflation expectations: Consumers and businesses may delay spending or investment, anticipating further price declines.

Monetary policy pressure: Persistent franc strength limits the SNB’s ability to tighten policy and may force interventions to support inflation.

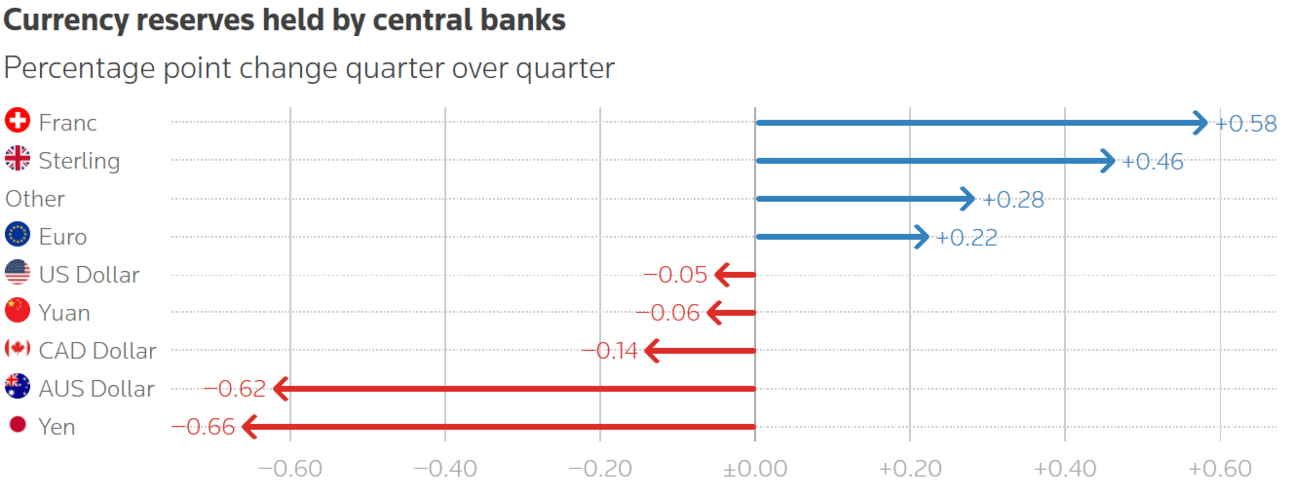

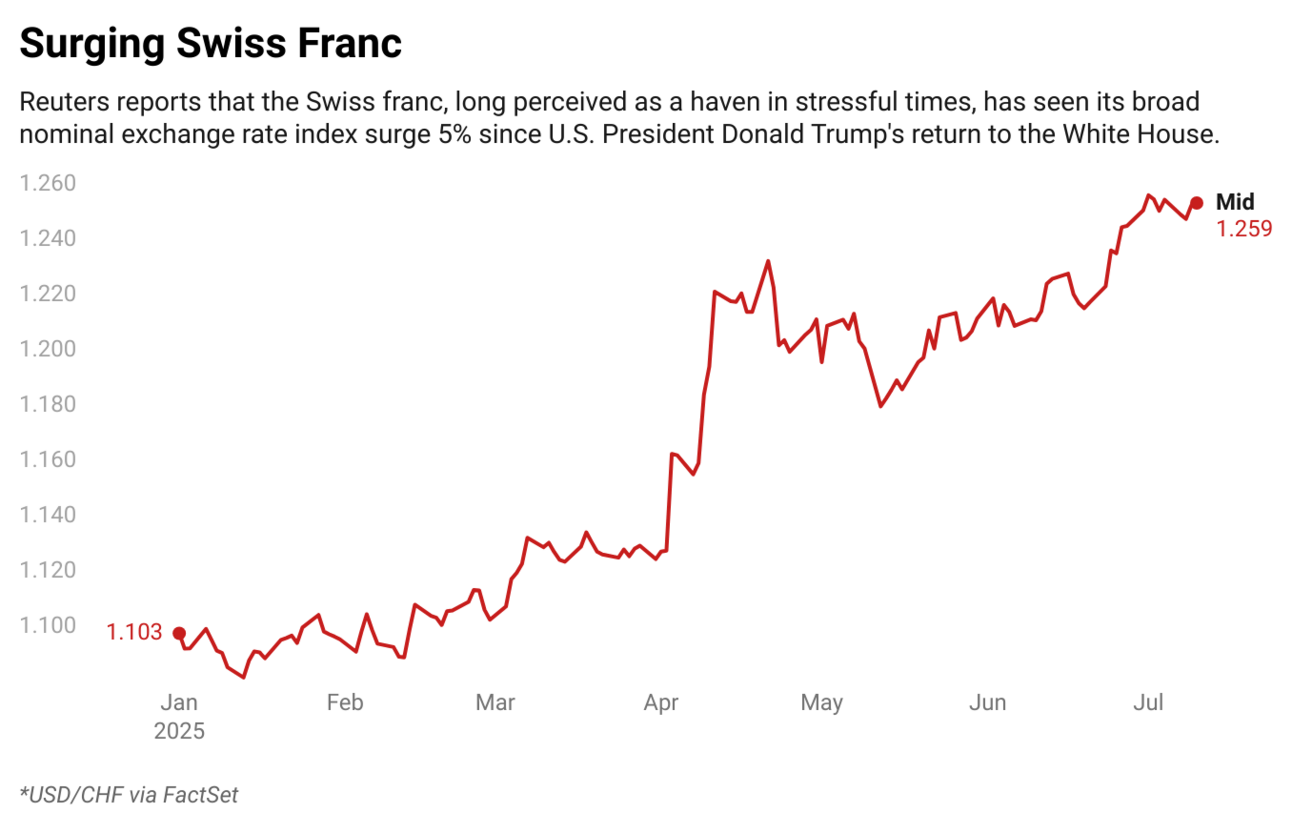

A rapidly appreciating franc dents demand for Swiss exports, which include luxury watches and pharmaceuticals. The franc has gained nearly 15% against the dollar since the start of the year, a rise that has lowered the price of imported goods and services and sent inflation spiraling downward. The franc has now quadrupled its share to 0.8% of central bank reserves by end-March - the highest level since at least 1999 when the euro was introduced. The SNB has signaled its readiness to take further action—potentially including a return to negative interest rates or foreign exchange interventions—but is holding off for now, citing concerns about the impact on savers, the banking sector, and political optics.

According to ING, Switzerland is already back on the U.S. Treasury’s Monitoring List for potential currency manipulation. A sustained period of foreign exchange intervention could lead to Switzerland being formally labeled a currency manipulator, potentially exposing it to trade-related penalties such as increased tariffs. Since 2020, the SNB has been required to report its FX interventions more transparently, publishing quarterly data with a one-quarter lag. Despite the political sensitivities, many expect the SNB will be compelled to intervene again if the EUR/CHF exchange rate approaches the 0.9200–0.9250 range. Any such intervention would likely target EUR/CHF rather than USD/CHF, as the SNB has limited capacity to influence the more liquid dollar market.

Source: FactSet

The outlook is expected to improve in 2026. Fiscal stimulus should begin to positively impact eurozone growth early next year, and by the second half of 2026, investors may start speculating about the first ECB rate hike. This could push the EUR/CHF exchange rate back toward the 0.97–1.00 range by late 2026 according to analysis by ING.

EUR/CHF vs. USD/CHF

The USD/CHF exchange rate reflects the economic and financial ties between Switzerland and the United States. As an important trade partner and issuer of the world’s primary reserve currency, the U.S. significantly influences this pair. Movements in USD/CHF are often driven by U.S. Federal Reserve policies, shifts in global risk sentiment—since the Swiss franc is considered a safe-haven currency—and international capital flows. A stronger franc against the dollar can reduce Swiss export competitiveness in the U.S. market and impact Swiss financial markets.

The EUR/CHF exchange rate reflects the economic and trade relationship between Switzerland and the Eurozone, Switzerland’s largest trading partner. This rate serves as a key indicator of Swiss export competitiveness within Europe. A weaker euro or stronger franc makes Swiss goods more expensive in euro terms, which can reduce demand from Eurozone countries. The exchange rate is heavily influenced by European Central Bank monetary policy and the overall economic health of the Eurozone.

Another Frankenshock Episode Unlikely

Both the current situation and the 2015 “Frankenshock” revolve around a rapid and significant appreciation of the Swiss franc, which puts strong downward pressure on inflation and export competitiveness. In 2015, the SNB unexpectedly abandoned its euro peg, causing the franc to surge almost 40% in mere minutes and triggering deflationary risks and economic disruption. Today, the franc’s strength amid global uncertainties is similarly contributing to negative inflation and challenging Swiss exporters. In both episodes, the SNB faces a delicate balancing act between defending price stability and managing the economic fallout from a strong currency.

The likelihood of another Swiss franc shock, akin to the 2015 episode, has been significantly reduced due to several key factors.

The SNB is now more transparent about its intentions and policy interventions, which helps temper market uncertainty and limits the potential for abrupt surprises.

Investors are already pricing in the possibility of further rate cuts and renewed interventions, reducing the shock factor. Importantly, the SNB has signaled that future actions will be based on broader price stability metrics, rather than reacting to isolated inflation data. Its current strategy also favors a gradual, step-by-step approach rather than sudden or dramatic policy shifts.

However, persistent risks remain. The Swiss franc continues to serve as a safe-haven asset, and any surge in geopolitical or financial market instability could prompt sharp capital inflows, potentially forcing the SNB into more aggressive action. Furthermore, with interest rates already near zero and a sizable balance sheet, the central bank’s toolkit is limited. Should external shocks or eurozone instability intensify, the possibility of abrupt moves cannot be completely dismissed.

While some analysts caution that another franc shock remains within the realm of possibility, most agree that its impact would likely be less severe than in 2015. The SNB itself acknowledges the risk of returning to negative rates or intervening again in currency markets, but it remains committed to a more measured and transparent policy trajectory.

Congratulations on making it to the end, while you’re here enjoy these other newsletters and be sure to subscribe to The Triumvirate before you go.

Interested in How We Make Our Charts?

Some of the charts in our weekly editions are created using Datawrapper, a tool we use to present data clearly and effectively. It helps us ensure that the visuals you see are accurate and easy to understand. The data for all our published charts is available through Datawrapper and can be accessed upon request.